Such was the volume of great stuff to choose from, I thought I’d begin the post with a roundup of ‘runners up’ — sixteen records which didn’t make my top ten, but which I also enjoyed, and some of which I think are truly excellent. (Sixteen is an arbitrary number, but it makes a pretty 4×4 grid.) After that, I’ll talk about my ten favourites in a bit more detail.

So, here we go…

The Runners Up

One of the best live music experiences I had this year was seeing Yo La Tengo play ‘You Are Here’ from their wonderful new album There’s a Riot Going On, on a cool late summer evening at End of the Road Festival. Their new album is peaceful and warm, stuffed with ideas yet never showy. No other band has so much talent and yet wears it so lightly. Fifteen albums deep and they’re still going ridiculously strong.

In a great year for jazz-related releases (see also numbers 6, 4 and 3 below), Kamasi Washington’s epic, searching Heaven and Earth naturally stood out, as did Idris Ackamoor and the Pyramids’ cosmic, genre-hopping An Angel Fell, the title track of which was one of my favourite tracks of the year. There were jazzy undertones, too, to parts of Eiko Ishibashi’s The Dream My Bones Dream, a smoky and layered collection of avant-pop songs produced by Jim O’Rourke.

There was a ton of great experimental-electronic stuff popping up all over the place this year, from Gazelle Twin to Eartheater to Lotic to Elysia Crampton. All provided engrossing listens, but the two stuck out most (in addition to numbers 10, 8 and 5 below) were Tim Hecker’s surprisingly minimal and unsettling Konoyo, built around manipulations of the sounds of a Japanese gagaku ensemble, and the experimental gospel album soil from Josiah Wise’s project serpentwithfeet, an utterly unique sound built around repetitive mantras and cutting-edge, Arca-like production.

I was really excited when Mountain Man announced their new album Magic Ship — their first, Made the Harbor from 2010, is a personal favourite. Their mostly a cappella music is full of the private joy of singing — it sounds like a rehearsal in a back room, three women taking simple pleasure in harmonising with each other. A great example of how music can be quiet, simple, small, and still really powerful.

There were plenty of great sunny weather records this year, and a long summer to go with them. Mélissa Laveaux’s Radyo Siwèl is full of life, drawing from Laveaux’s Haitian heritage to reimagine Creole folk songs as sprightly, spiky, electric anthems. (This really nearly made my top ten; it’s ace.) Kadhja Bonet stewed up some psychedelic soul on Childqueen, the perfect laid back album for a late summer evening; ditto Khruangbin’s wide-ranging Con Todo El Mundo, which travels all over the musical globe while remaining remarkably chilled out.

One of my favourite obscure bandcamp finds this year was Cult Party, whose album And Then There Was This Sound is the best thing you definitely haven’t heard this year. Homespun folk stretched out into weird and wonderful shapes, especially on the twenty minute long opening track ‘Hurricane Girl’. Similarly elastic was Sandro Perri’s In Another Life, a kind of ambient-lounge-pop record where songs sprawl and unwind (the title track is nearly twenty-five minutes long) without losing interest.

Ryley Walker kept busy this year, putting out the downbeat, subtle Deafman Glance, in addition to the more unexpected move of covering Dave Matthews Band’s The Lilywhite Sessions in its entirety. Mary Lattimore also had another busy year; in addition to the dreamy, unfussily detailed harp-and-electronics excursions on Hundreds of Days, she also put out a great collaboration with Meg Baird from Espers, Ghost Forests.

Finally there were some great indie rock releases this year to keep the eternal indie-loving kid inside me happy. Beach House continued to find new shades of their dream pop sound with 7, while Mitski put out a great record with Be the Cowboy, which has been dominating a lot of the critics’ end-of-year lists, and about which I can only add that yes, I agree, it’s great.

So, those are the runners up. A lot of incredibly good stuff, and enough on their own to declare 2018 a decent year for music. And yet, there are ten more still to come. The following ten albums were all challenging, rewarding and moving in totally different, unique ways. I highly recommend them all. Let the countdown begin…

The Top Ten

10. Yves Tumor – Safe in the Hands of Love

This is one of the darkest, most anxious records I’ve ever heard. It would be difficult to describe it as a pleasurable listen, but it is certainly an affecting one. “Safe in the hands of love, that’s where I feel the pressure”, Tumor sings on the unexpectedly catchy lead single ‘Noid’. That lyric seems to capture the whole sound-world of the album — the sound of danger invading safety, of a previously safe space collapsing in on itself. The anxiety gathers itself up over the first six tracks, from the distant horn fanfare of ‘Faith in Nothing Except Salvation’ to the more explicit cries and worries of the three vocal-led, poppier tracks in the centre. The rest of the album that follows seems to disintegrate, giving over to layers of almost unlistenable noise, and yet the track titles (‘Hope in Suffering’, ‘Let the Lioness in you Flow Freely’) suggest a kind of overcoming. It’s like a storm stripping a building of all its contents and concrete, leaving just the metal frame, bent and reimagined into new shapes.

9. Adrianne Lenker – abysskiss

This is a subtle, nuanced record, the bones of which are just guitar and voice. Yet despite those simple ingredients, it sounds just as genuinely new and exciting as anything else on this list. Lenker’s unique voice — both literally and figuratively — imbues her record with such exquisite emotion, it almost makes other records sound dishonest by comparison. Her guitar playing is also quietly astonishing, full of detail. I love her band Big Thief (their brilliant album from last year, Masterpiece, has grown on me a lot) but I’m tempted to say Lenker’s solo stuff is even better — it really highlights her unique approach to melody and texture. There are very subtle backgrounds to these songs, bedrocks of piano or synth, which are so far back in the mix they become almost like atmosphere, like the ambient noises of imagined rooms. And indeed this is an involvingly atmospheric record, an immersive headspace best experienced on a quiet evening, in low light, in rapt attention.

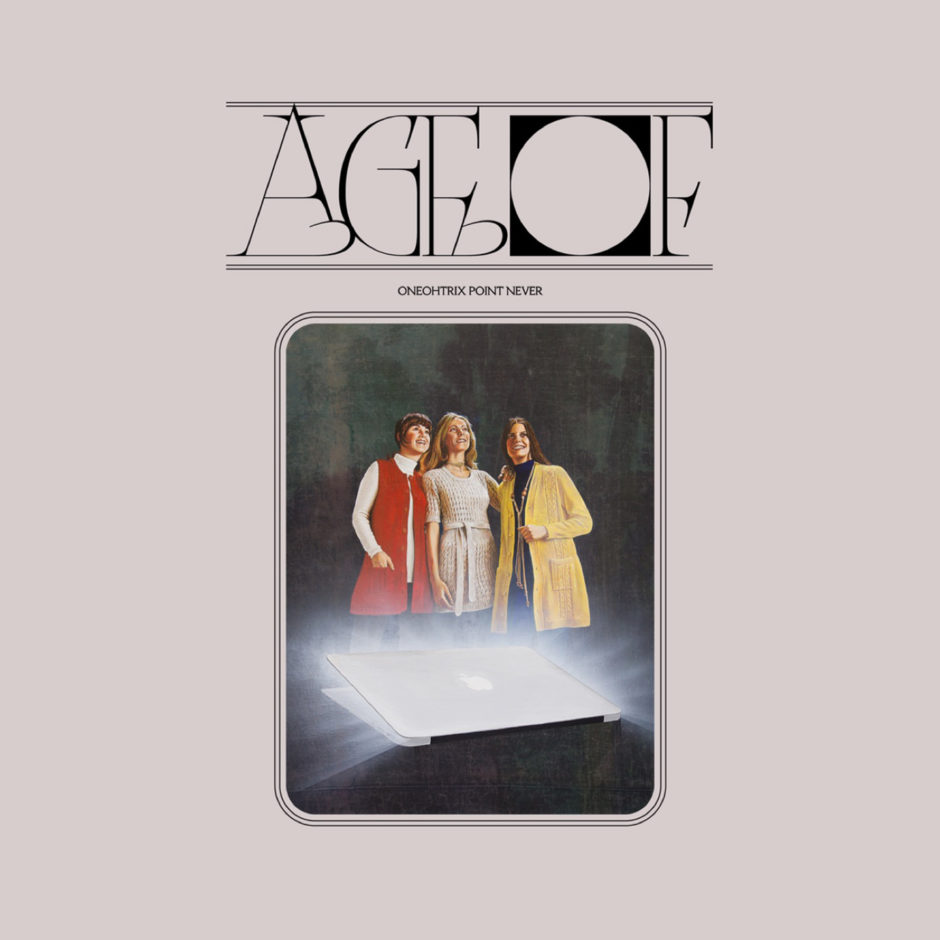

8. Oneohtrix Point Never – Age Of

In comparison to some of his previous work, Age Of feels fairly slept on, which is a shame, as I think it’s among the best things Daniel Lopatin has ever made. It covers a huge amount of musical ground: most obvious are the addition of new age sonics to the sound palette, audible on pieces like ‘RayCats’ and the title track, and the introduction of upfront (albeit heavily processed) vocals on tracks like ‘Black Snow’, ‘Babylon’ and album highlight ‘The Station’. Yet the album also brings back elements from each of his previous experiments: the plunderphonics of Replica, the digital glitch-fest of R Plus Seven, the teenage angst of Garden of Delete, from which ‘Warning’ feels directly lifted. In its breadth, Age Of feels like the culmination of Lopatin’s war against what he calls ‘timbral fascism’, the idea that certain sounds are inherently more musical than others. For despite its occasional difficulties and sharp edges, it is really a very musical album, full of gorgeous melody and harmony, and deeply evocative sound-worlds. No one else makes music like this, and we shouldn’t start taking it for granted just because this is something of an OPN highlights reel, rather than a brand new direction.

7. Amen Dunes – Freedom

Amen Dunes’s songs are like tightly coiled springs of indie rock brilliance, simmering with under-the-surface energy. They’re all cool on the surface and bubbling underneath. In many of these songs, tension seems to build and release simultaneously — I wish I had a better technical knowledge of music to understand how he creates this effect, but I find it incredibly addictive. Album highlight ‘Believe’ — by some considerable margin my favourite song of the year — builds and builds, piling on great idea after great idea, without ever quite boiling over. I don’t know how he does it. There are just so many fantastic scraps of melody stuffed into one tiny song without it feeling overworked. Elsewhere, ‘Blue Rose’ shakes with gritty confidence, ‘Calling Paul the Suffering’ skips around and bops, and ‘Skipping School’ and ‘L.A’. are the sound of an open road captured on tape. The lyrics explore masculinity, the complexity of ‘bad boy’ figures (‘Satudarah’ and ‘Miki Dora’), and, above all, the many meanings of the word freedom. A great follow-up to the also excellent Love from 2014. He’s great live, too.

6. Park Jiha – Communion

Like Yo La Tengo’s record, Park Jiha’s Communion offered peace and humanity whenever I needed it this year. It was an album to return to when I needed a glimmer of light. Sitting somewhere in a nexus between jazz, classical minimalism, and traditional Korean music, this is maybe the most straight-up beautiful music I have heard all year. Tracks like ‘Sounds Heard from the Moon’ and ‘Accumulation of Time’ are shimmering, Reich-like sheets of yanggeum, a hammered dulcimer. Better still are the pieces using piri (a double reed bamboo flute) and saenghwang (a mouth organ), which imbue the music with breath and life. The intense, gorgeous title track is a highlight, as is the serene ‘Longing of the Yawning Divide’. The last two pieces then bring the reeds and dulcimer together, climbing cosmically towards the record’s climax. Magnificent stuff.

5. SOPHIE – Oil of Every Pearl’s Un-Insides

Some records — like my favourite album of last year, Richard Dawson’s Peasant — take us back into the distant past. SOPHIE’s album instead takes us to a distant, imagined future, to a ‘Whole New World/Pretend World‘, a world where materials have become completely plastic, where anything is able to transform into anything else, or to stop mid-transformation and remain in a kind of molten, ambiguous physicality. SOPHIE uses sound itself to create this world, melting genres together, splicing together different sounds on an almost molecular level. She imbues her music with such incredible physicality (seriously, I don’t understand what she’s doing to the sound to make it sound so physical) and yet her productions have no tangible relation to any specific source in empirical reality: they seem to exist in an entirely digital sphere. The album is also incredibly well sequenced: a true journey across different soundscapes, sometimes evolving gradually and sometimes turning with whiplash speed from one style to another. It is thrilling. I have never heard anything like it.

4. Lonnie Holley – MITH

This is a hugely ambitious record from Holley, an outsider artist who makes junk sculptures from recycled found objects. (Such art is a personal obsession of mine, ever since I first accidentally stumbled across Isaiah Zagar’s Magic Gardens in Philadelphia). The approach to sound on MITH is in some ways similar to junk sculpture: rooted in spiritual jazz, the album is yet another (albeit wildly different) example of the melting and melding of different styles. Its sound is exploratory, occasionally psychedelic, and always searching. It is also a very political record, a state-of-the-nation document of America in 2018, as most powerfully felt on its grandest, hungriest tracks: the growling ‘I Woke Up in a Fucked Up America’ and the incredible, eighteen-minute centrepiece ‘I Snuck Off the Slave Ship’. But I find it just as captivating, and just as emotionally affecting, in its quieter moments, too, like the trippy ‘How Far is Spaced Out?’ and the demented lounge of ‘There Was Always Water’. This is powerful, remarkable music.

3. Sons of Kemet – Your Queen is a Reptile

Your Queen is a Reptile is an exploration of rhythm, and of the possibility that rhythms can carry ideas. Like Holley’s, this is a very political album, this time dealing with the currently chaotic state of the UK. It feels like the first truly post-Brexit album (a description which might put you off, but shouldn’t). Yet despite some vocals on the first and last tracks, and the nods in the track titles to women of colour (‘My Queen is Ada Eastman’, ‘My Queen is Harriet Tubman’, ‘My Queen is Angela Davis’ etc.), the majority of Sons of Kemet’s ‘message’ is carried in the rhythm. This is passionate music, filled with both anger and defiant hope, made by people searching for a place to belong in a country that seems to have voted them out. The two drummers (Tom Skinner and Eddie Hick) layer rhythms from jazz, funk, punk, dub, reggae, and various African musics into a storm of percussion, which the horns are able to leap off of and build on; indeed, Theon Cross’s infectious tuba playing is a big part of the album’s rhythmic appeal too. The tenor saxophone of Shabaka Hutchins — one of the central figures in the UK jazz scene, who’s played with The Comet is Coming (who are also ace if you’ve never checked them out) and Shabaka and the Ancestors, and who put together the compilation We Out Here — provides the music with its wings. Most impressive is the fact this album just does not let up — it just gets better and better as it progresses, building to almost an hour of infectious, insatiable music.

2. Low – Double Negative

Having been a huge fan of Low for over ten years now (which still makes me a relatively young fan of the band; they’ve been around for nearly twenty-five), it has been exciting and strange to see them suddenly getting so much attention for their new album. Partially this attention is because it’s excellent. But it’s also partially, I think, because the album has a slightly easy narrative around it: long-running, well-respected band responds to Trump’s America by destroying their old sound with electronics, tearing it apart, descending into fragments and distortion in order to reflect the chaos of the current climate. The reviews practically write themselves. So it’s an easy album for critics to love; perhaps almost a bit too easy. And that is my one reservation about it: that, in fact, Low have always been an interesting, experimental band, who have always rebuilt their sound up from the ground each time; that underrated albums like 2013’s The Invisible Way, which made use of piano in a way Low had never previously explored, or 2007’s Drums and Guns, which also had some really unusual production choices, were just as interesting and just as worthwhile as Double Negative, even if they weren’t as easy for critics to write about.

So there’s my caveat. Now for the more important bit: Double Negative is ridiculously good. Just ear-meltingly brilliant. A complete, immersive sonic experience. I cannot get over how good it is. The production is astonishing, the layers of distortion and noise conveying so much emotion — I don’t think I’d ever realised there were so many different kinds of distortion before. More importantly, the songs are incredibly strong throughout, emerging out of the noise in continually unexpected ways, and packed with Low’s always brilliant melodies and signature two-part harmonies. I couldn’t possibly pick a highlight: the whole thing needs to be heard front to back. This thing sounds cavernous in places, yet it never loses a sense of intimacy. There are tiny touches — like the rasping-for-breath synth that comes in about 1:12 into ‘Dancing and Blood’ — that catch me by surprise every time. A totally unique album that I’ll be returning to for years to come.

1. Julia Holter – Aviary

With Aviary, Holter has crafted a huge sonic world to explore. It really does feel less like you’re listening to an album, and more like you’re wandering around in a vast landscape, full of gnarled trees, strange birds squawking, medieval monks chanting, massive clouds moving over the tops of mountains. Holter has talked about how the record doesn’t necessarily need to be listened to all the way through (though I’d add that it is very well sequenced if you choose to listen to it that way); rather, the listener can find their own path through it. What’s most impressive, though, is that she has created this wholly immersive experience not using fancy interactive apps or VR headsets, but simply using sound. The combination of sounds on this record make it sound truly three-dimensional, almost non-linear. I don’t feel like I play through the album, but like I play around inside it. This was maybe the defining feature of much the music I enjoyed this year. I’ve said similar things about SOPHIE’s record, about Lonnie Holley’s, about Oneohtrix Point Never’s; even Low’s album might be seen as making their sound less linear, more exploratory and explorable. These are albums that are playful in their combination of genres and ideas, and that feel, as a result, almost interactive in the way they are experienced by the listener. They are truly, in every sense of the word, worlds of sound, waiting to be explored and uncovered every time you press play.

Holter pushed this idea further than anyone else this year. The quality, variety and imagination on display across this album blows me away every time I hear it. It is a colossal, absurdly ambitious record, an hour and a half of almost limitless creativity, in which centuries-old musical ideas and languages are melded imperceptibly with modern synthscapes, elements from free jazz, krautrock, and a whole variety of other 20th and 21st century traditions, all wrapped up in breathtakingly beautiful songs. The overwhelming beauty of it — the generousness of that beauty — reminds me of Bjork’s Utopia from last year, and yet there are also passages of confusion, density, almost horror. It is cathartic and transcendent. It crowns a discography — running from Holter’s 2011 debut Tragedy, through the brilliant Ekstasis in 2012 and Loud City Song in 2013, to her breakthrough Have You in my Wilderness in 2015 — which is unmatched by anyone else this decade. It has been an absolute pleasure to follow along since 2011 and see her develop as an artist. And though Loud City Song remains (I think) my personal favourite, Aviary feels like the culmination of everything she’s been building towards. It is a towering achievement, and, to my mind, the most essential album of 2018.

Thanks and Playlist

So there we are. Thanks for reading. I hope this has helped you discover something new that you’ll enjoy and that you haven’t heard before. To that end, here’s a Spotify playlist with a track from each of the albums I’ve mentioned, plus a few others to round it up to an even 30. Spotify is great for discovering things, but please support the artists and buy the music if you like it.

I’ve been really quiet on the blog this year, but I promise I haven’t abandoned it entirely. Indeed, one of the reasons I called it The Quiet Return is because I don’t see it as a place I have to constantly worry about generating new content for (I don’t want to write things just for the sake of it), but simply a place where I can come and reflect when I feel I have something to say: a place I can quietly return to. Having said that, I’m hoping to beat my very low bar of two posts next year and put a few more things up! So hopefully see you again here in the new year.

For now, happy Christmas, and happy listening…